The Discovery of El Greco: The Nationalization of Culture Versus the Rise of Modern Art (1860-1914) tells the fascinating story of the meteoric rediscovery of El Greco towards the end of the nineteenth century. Here, author Eric Storm introduces the discovery of El Greco and its importance in the world of modern art.

Domenikos Theotokopoulos, the real name of El Greco, was a religious painter of the Counter-Reformation. After having been largely forgotten, he surprisingly became an important source of inspiration for impressionist painters like Eduard Manet and Edgar Degas, and was even seen as a crucial precursor and heroic visionary by avant-garde artists such as Pablo Picasso and the expressionists of the Blue Rider. El Greco came to be seen as a quintessential Spanish painter, despite being born and raised as an Orthodox Christian on the island of Crete, receiving his training in Venice, and only coming to Toledo, Spain at around the age of 35. He became the main precursor of Diego Velázquez and was considered one of the great representatives of the Spanish School. Surprisingly, the nationalization of El Greco was closely entangled with the growing appreciation for his art among avant-garde circles.

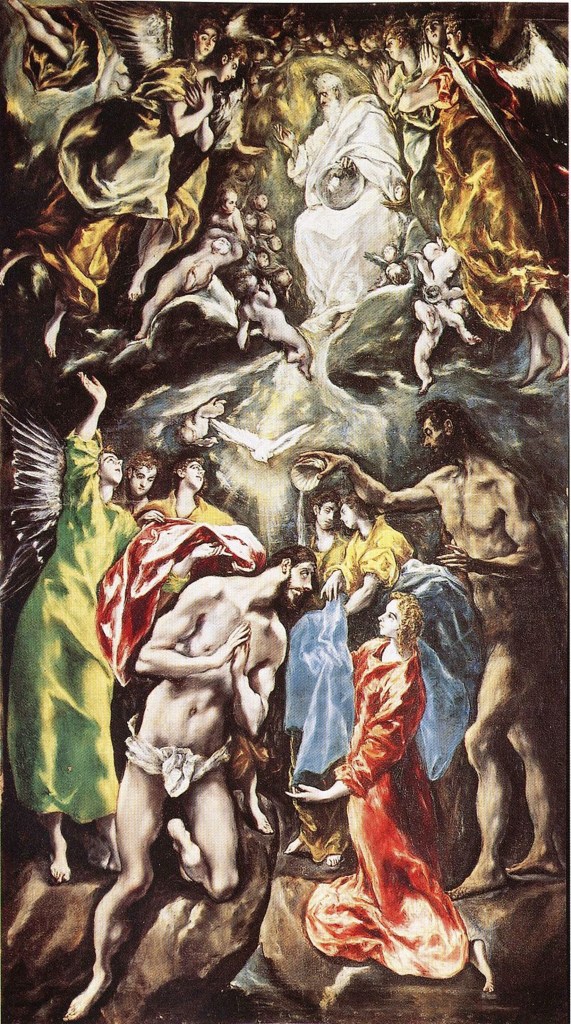

El Greco (1541-1614) came to Spain in the hope of being commissioned for King Philip II’s new Escorial Palace. However, his Martyrdom of Saint Maurice (1580-182) [Fig. 1] failed to impress the king, possibly because the crucial event of the actual martyrdom was painted in the background. Nonetheless, El Greco would have a very successful career in Toledo, the seat of the archbishop of central Spain. Many churches still have impressive baroque altars [Fig. 2] from his hand. However, his elongated figures, lively colours and expressive compositions fell out of favour with successive generations. Some even argued that he became mad or suffered from an eye disorder.

The rediscovery of this strange, largely forgotten artist was an international affair. Impressionist painters in France, like Manet and Degas, were fascinated by the realism of Spanish seventeenth-century artists and by El Greco’s innovative depiction of light. Manet clearly felt inspired by El Greco’s Holy Trinity (1577-79) [Fig. 3] for his own Dead Christ with Angels (1863-64) [Fig. 4].

A crucial role in the dissemination of his fame was played by the German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe, whose travel report The Spanish Journey (1908) was almost entirely dedicated to his discovery of a relatively unknown genius, who according to him was one of the greatest precursors of modern art: El Greco. Inspired by Meier-Graefe, Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky decided to include a painting of El Greco as the only old master in their almanac of The Blue Rider (1912) [Fig. 5].

Shortly afterwards, at a path-breaking modern art exhibition in Cologne, John the Baptist was displayed in a room dedicated to Picasso, while another Greco hung in a room reserved for the work of Van Gogh.

So far the story is more or less known, at least to experts. However, art historians have largely ignored that besides the modern art connection, El Greco was also nationalized. Although he continued to sign his paintings in Greek, as a consequence of the rediscovery of his work he was turned into a truly Spanish painter. Surprisingly, it was not so much Spanish scholars and artists that hispanized him; a crucial role was played by critics and painters from other parts of Europe.

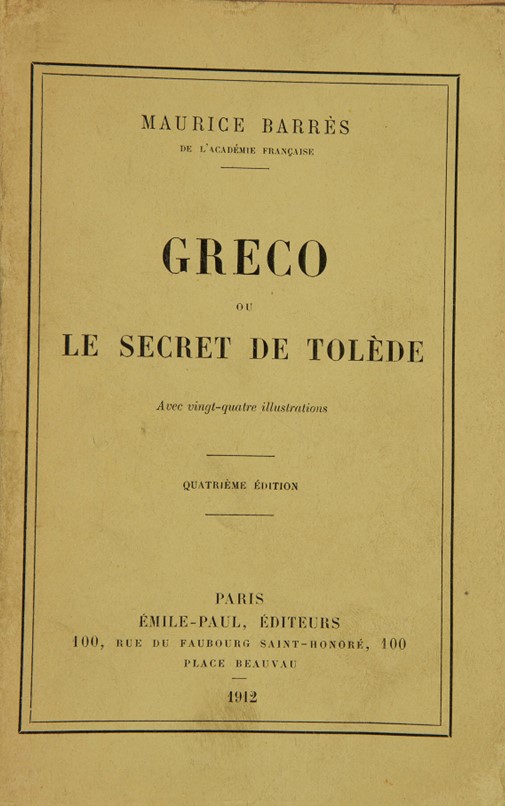

Even during the nineteenth century, British, French, Spanish and German art historians published historical overviews of Spanish art in which they awarded El Greco a place in the early phases of the Golden Age of Spanish painting. The famous French nationalist author Maurice Barrès even dedicated an entire book to the painter [Fig. 6], in which he presented his mystical paintings as fundamentally in line with a deeply rooted Spanish Catholicism.

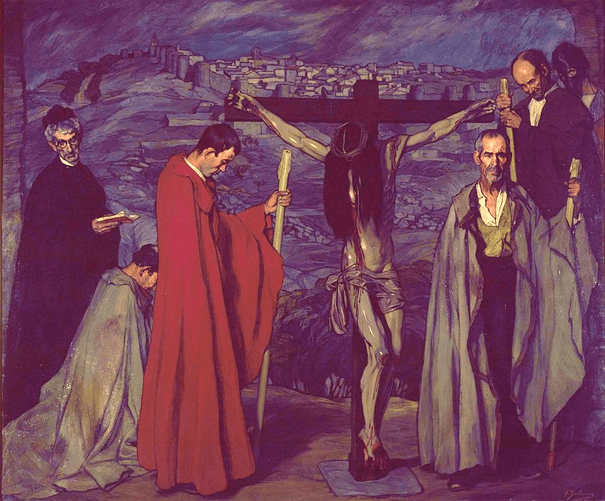

During his stay in Toledo he found that the Spanish national spirit was still very much alive and in his book he presented the inhabitants of the old city as a shining example to his own compatriots, who, according to him, had largely lost contact with their own national traditions. Barrès was portrayed before Toledo [Fig. 7] by the Spanish-Basque painter Ignacio Zuloaga, who in a very similar way connected the memory of El Greco to Spanish national traditions [Fig. 8], for instance by depicting a procession before the walled Castilian town of Ávila.

This process of this hispanization of El Greco culminated in the opening of a museum in his fancifully restored house in Toledo, and the highly nationalist commemoration of the tercentenary of his death in 1914.

This is explored in more detail in Eric Storm’s book, Discovery of El Greco: The Nationalization of Culture Versus the Rise of Modern Art (1860-1914), which is a comprehensive study of the rediscovery of El Greco, examining the work of painters, art critics, writers, scholars and philosophers from France, Germany and Spain, and the role of exhibitions, auctions, monuments and commemorations. Learn more about this book on the LUP website.

Eric Storm lectures European History at Leiden University. His research interests include Spanish history and the construction of national and regional identities in Europe. He is the author of The Culture of Regionalism: Art, Architecture and International Exhibitions in France, Germany and Spain, 1890-1939 (2010), La perspectiva del progreso: Pensamiento politico en la España del cambio de siglo (2001), and Nationalism: A World History (2024).

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk