Each year our Pavilion Poetry students assist with the publishing of our new collections, dedicating their time to an individual poet. Within this interview, author Sarah Corbett discusses her new collection, The Ishtar Gate (Pavilion Poetry, 2025).

The Ishtar Gate is your sixth collection of poetry. How has your understanding of poetry’s role in the world evolved since your debut?

Poetry has always held an important role in world, not only in the political sense but in how poetry affects our somatic bodies, our states of mind, and allows us to the see others and the world in new or radically different ways. Poets are ‘the unacknowledged legislators of the world’ as Shelley put it, whether this is of the inner world of the heart or the external world of histories and events. As a creative act of witness, poetry remains uniquely placed to speak the truths of our individual and collective experience.

One major evolution in poetry in the twenty odd years since my first collection The Red Wardrobe was published (in 1998, but written during the early – mid 1990’s) is the focus on environmental issues and the emergence of ‘eco-poetry’ as a new genre. This has brought a higher profile to the role that poetry can play on the stage of world events. Perhaps for the first time since the second world war, poets in the West have had something serious to write about. Of course world poets have always had major challenges to respond to, whether this is the poets of Russia and Eastern Europe writing in secret or being imprisoned during the repressions of the Soviet Regime, or poets writing from within the devastation of war. The prominence of poets and poetry in war-torn Iraq and now Palestine and Ukraine, attest to the continuing importance of poetry in times of extreme historical duress.

Some of the biggest changes in how poetry’s role in the world has changed in the English-speaking world have been in the rise in prominence of women’s voices, and the opening of opportunities for diverse voices. These poetries are increasingly vocal in the world, with many contemporary poets engaged through their work in some form of social or political activism. Auden’s claim that ‘poetry makes nothing happen’ can be seen nowadays to be largely debunked. Poetry very often makes things happen and is increasingly a force that challenges the status quo and directs us towards new ways of being.

The book opens with an invocation to the goddess Ishtar and closes with her rising from a spring thirty years in the future. What drew you to Ishtar as a guiding figure, and how does she shape the collection’s narrative arc?

The central importance of Ishtar as a guiding figure for the collection lies in the story of her death and rebirth. The cycle of death and rebirth is one of the universal motifs in the human journey, a cycle of dissolution and regeneration that all humans, and all human/historical events travel. Each new creative journey is a journey to the underworld and back. This is often true for poets, and why the story recurs in many of the West’s great poetic works (e.g. Virgil’s The Aeneid, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus). My new collection The Ishtar Gate aims to move the reader from a symbolic/historic death towards a creative, imagined rebirth.

For many years now I have been visiting the spring that emerges in the fields near my house and leaving small offerings to the divine female spirit, or goddess of springs. The image of the goddess rising from the spring came very early on in the writing of the third part of the book. That a female deity opens the book and closes it felt to me to be an intuitive, creatively important ‘surprise’ in the way that only a poem, and the process of writing poetry, can surprise the poet.

Ishtar is a goddess of war and love. Book I of The Ishtar Gate very much draws on war and the devastation it leaves – death, grief, hauntings; but love is also present. Book II continues to work with both of these universal themes. Love in its many forms, and the connections love forges is one of the redemptive threads of the book. It is these resonances, synchronicities and correspondences that I encountered and uncovered through the image of the goddess as the three parts of the book evolved, that weave through the collection and bind its various themes, concerns and environments together.

You explore the collision of self and history across different times and places. How did you decide which historical moments to include?

I always knew that the writing of book would start with the fall of the Berlin Wall. This is the moment, for my generation, when history changes. For this present generation that moment is 9/11. Then again, perhaps the war in Ukraine will come to define the key fissure on this current historical cycle, which began with the fall of the wall 1989. What followed in 1989 was the collapse of the Soviet Union, and from this the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the start of the Balkan wars. This was the period of my twenties, of becoming an adult and emerging as a young poet, highly politicised and historically aware at a time of seismic historic shifts. I grew up through the cold war and the perennial threat of nuclear war, which played its part in the breakdown I suffered in 1989 and is pointed to in the ‘Leeds’ sections of ‘Berlin’ in Book 1 of The Ishtar Gate. I lived for a year in Prague in 1993 not long after the Velvet Revolution of 1991 ousted the Soviets from Czechoslovakia, and witnessed first-hand how a people and communities survived and emerged from a repressive regime. Although I’ve written about some of these experiences in my third collection, Other Beasts, (published by Seren books in 2008), I wanted to revisit them in a different way, and to consider how this period in history shaped me as a poet.

What do you hope readers feel when encountering these fractured histories and selves? Is there a particular emotional or intellectual response you’re aiming to evoke?

It’s poetry’s job to send a depth charge into the psyche of the poet, the poem, and by extension, the reader. Poetry is neither history, polemic nor political tract. It can only hope to reveal hidden patterns where personal histories and experiences intersect with the known and experienced world, and historical events themselves as they impact us individually and collectively. Poetry can only do this by being selective, and by working though images and metaphors that call up deeper knowledge and understandings. What is glimpsed or intuited, as well as what is experienced or ‘known’ through more conventional mediums that are themselves part, partial and/or partisan (such as news reports, recent histories, or collective memory). I hope my reader will encounter these poems and fragments, sequences and correspondences both on their own terms – as poems to be enjoyed for their different affects, whether evoking grief, nostalgia, or love; as visual and imaginative journeys; and as a ‘map’ to the convergences of historical processes that can feel frightening and beyond our control as they are happening to us, pass through or by us. The book hopes to offer spaces and images of silence and connection that might bring joy, hope or solace in these challenging historical times, and point the reader, if they so wish, to explore further the artistic and historical sources the book evokes and draws upon.

The imagery of the ‘Red horse of time, white horse of poetry, blue horse of dreams’ is vivid and compelling. How did you arrive at this symbolism, and what do these horses represent in relation to time, creativity, and the human imagination?

In simple terms the three colours of the horses refer to the red, white and blue of Kieslowski’s film trilogy ‘Three Colours: Red, White and Blue’, which in turn refer to the French flag and how it represents freedom, equality, fraternity. That this also reminds us visually of the British flag, and of flags and the notion of nationhood in general, is not incidental. Abramović, for her seminal performance piece ‘The Artist is Present’ wears in sequence a red dress, a blue dress and a white dress – the colours of the Serbian flag. In another piece, Abramović sits on a white horse bearing a white flag.

Horses have featured in human lives and throughout human time since we hunted them for food and then trained and domesticated them; they have carried our histories – and wars – on their backs. The ‘red horse of time’ recalls in part one of Joy Harjo’s mythic red horses, and relates perhaps to a universalising force that we cannot control, one that is both mysterious and terrifying but that is always moving us forwards, always moving us back.

Sarah Corbett has published five collections of poetry, including ‘A Perfect Mirror’ (Pavilion Poetry, 2018), and the verse-novel ‘And She Was’ (Pavilion, 2015). She is Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing for Lancaster University and lives in Hebden Bridge.

Follow @pavilionpoetrylup on Instagram and visit our website to pre-order The Ishtar Gate.

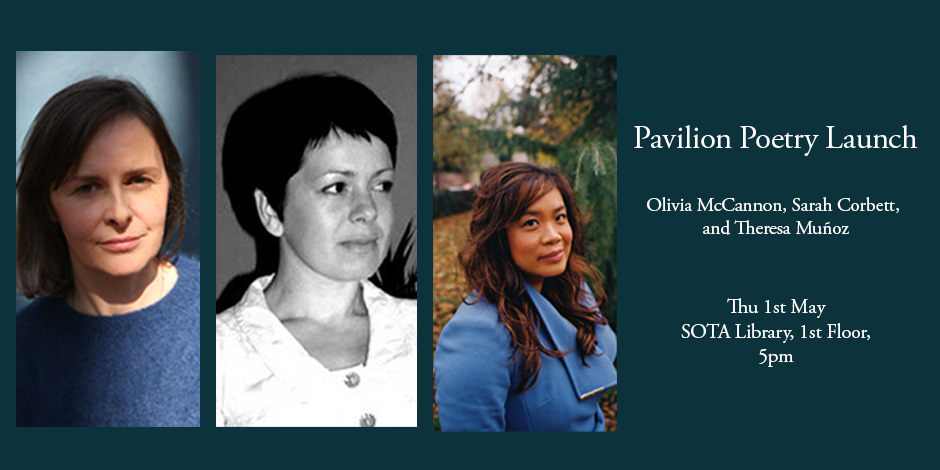

Pavilion Poetry Launch 2025

Join us in Liverpool on Thursday 1st May to launch our new collections from Olivia McCannon, Sarah Corbett, and Theresa Muñoz with the Centre for New and International Writing. Register for the free event here.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk