Each year our Pavilion Poetry students assist with the publishing of our new collections, dedicating their time to an individual poet. In this interview, Sarah Herbert talks with author Olivia McCannon about her new collection, The Lives of Z (Pavilion Poetry, 2025).

What led you to explore the connections between language and ecology in the poems of The Lives of Z and where did this take you?

The poems of The Lives of Z question all kinds of ‘authoritative’ structures and systems, and their impact on past, present and future forms of life on Earth.

One of my starting points was that English, the language itself, is a ruin. That English is marked by the many kinds of destruction in which it is instrumental. The damage is reabsorbed, compromising its structures.

I asked myself why I would a) write poetry b) write in English, on a damaged planet. How could my writing reinvent what it was for, to better serve the needs of life?

‘Life’ also exists in language. For some humans, English feels cramped, for others it feels spacious. Some kinds of being are barely present at all.

However immovable it looks, a language, like many systems, is also a series of choices. You can choose differently, you can wobble it, widen its cracks.

Am I allowed to change my language? If not, who or what am I allowing to change it for me?

What does “Z” represent – an entity, an idea, or something more fluid and undefinable?

I felt that the world had become unreadable, and I didn’t know what to write back with.

I found myself writing as a translator. When you translate a poem (a piece of creative life), you ask it questions, from a place of not knowing or understanding. You also work with what is inescapably there on the ground.

Z emerged from a desire to acknowledge and move through fear, paralysis, elegy, in search of breathing space, to find active and creative forms of hope, regeneration and resistance.

Z became an invitation to foreground the unexpected clusterings of co-existence, in a language perhaps more comfortable expressing individualism than fusion and transformation. To tune into the generative, inventive, unbiddable principle of creative life on Earth.

Did the speculative mode of these poems help you to write more adventurously?

I’m pretty sure that reading SF and speculative fiction by, among many others, Ursula K. Le Guin, N.K. Jemisin, Joanna Russ, Octavia Butler, Kim Stanley Robinson, Richard Powers, Marie Darrieussecq, gave me much-needed permission to dust off my poetic licence.

Above all, the Z poems wouldn’t exist without the irrepressible, witty and inventive writing of the Québécoise (eco)feminist writer and poet Louky Bersianik (1930–2011).

Her work creates an ‘archaeology of the future’, excavates alternative civilisations in the feminine, to ‘break the sequence of the archaeological past’, redefining what it can mean to be ‘human’.

She looks backwards and forwards simultaneously and I have done this too. Experiencing a present reframed by distant or deep time, through archaeological or geological perspectives, can feel equally if not more speculative and disruptive.

The kind of vision I’m drawn to is one where all times are nested, all places connected.

In a humanless future where other-than-human life is thriving, what does the human, its last finite traces transformed by temporal and (un)natural processes, look like now? Who or what owns this story and the objects that tell it?

The poems are peppered in places with what look like scientific words. In what spirit do these appear?

A year or so ago, I found myself trying to explain what I was doing with these poems, to a scientist with many patents to his name. After a short pause he said, “this sounds like bad science to me”. I was delighted when it dawned on me that he had gifted me a brilliant, honest, description of my work.

I wanted to be better informed about the climate and biodiversity crises, and turned, as a beginner, to scientific research and writing. I kept stumbling over newly named concepts and terms-under-construction (such as ‘Anthropocene’).

These were potentially immensely useful ideas and words. However, I didn’t know how I would or could use them, as a lay person.

I was curious to see what happened if I mixed them up with scraps of other language and life in poems. How might they change (for better or for worse)? What might grow out of them?

The Z poems aren’t so much learning science, as trying out new forms of language, or becoming language-in-the-process-of-changing.

There are also terms lifted out of other kinds of English within English (legal, financial, bureaucratic, techy), which are in there for the stories they tell about systemic power.

In a poem that seems central to the project (“Letter”), the reader is invited to “play Z’s game”. Why?

For many reasons, but here are a few.

Playing in a language gives you permission to move, breathe and turn, even in the tightest spaces. A poem is a safe space in which to try out something new.

A poem is a co-operative invention. If the reader doesn’t invent along with the writer what a poem is for, it remains a beautifully patterned silence.

Earthly life is co-creative, it clusters and grows through meshing networks, makes space out of connections.

The life of the reader meeting the life of the writer in the ground of the poem creates the continuity of life passing itself on. This can be a form of resistance that speaks back to the deadliness of finitude and the isolating divisions of power.

The poems aren’t ends in themselves but joinings, sending to the collective change that is already happening. They are deliberately porous, made of holes and portals, there are strands left sticking out of the text for the reader to pick up, if they want to.

Earth itself is not a plaything. Z’s lives want afterlives.

Listen to an audio recording of Olivia McCannon reading her new poem Letter (surface debris) below:

Olivia McCannon is a writer and translator. Born on Merseyside, she has lived in Paris, London and elsewhere. Her first poetry collection, Exactly My Own Length (Carcanet), won the Fenton Aldeburgh Prize and was shortlisted for the Seamus Heaney Centre Prize. Her translation of Balzac’s Le Père Goriot (Penguin Classics) was selected as one of Boyd Tonkin’s 100 Best Novels in Translation. Recent work has appeared in Dark Mountain, PN Review, MPT and Shearsman magazine. The Lives of Z emerged from AHRC-funded doctoral research at Newcastle University.

Follow @pavilionpoetrylup on Instagram and visit our website to pre-order The Lives of Z.

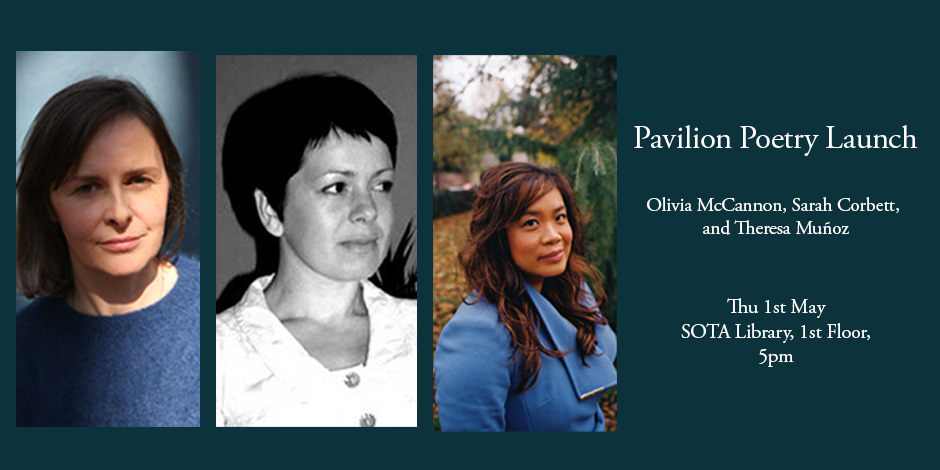

Pavilion Poetry Launch 2025

Join us in Liverpool on Thursday 1st May to launch our new collections from Olivia McCannon, Sarah Corbett, and Theresa Muñoz with the Centre for New and International Writing. Register for the free event here.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk