The Book of Kings is a universal history and capstone to the chief scripture of the Mandaeans, the only surviving Gnostic community from Late Antiquity. For the first time ever, it has been published in English in its entirety, directly translated from original Mandaic manuscripts with a scholarly commentary. Charles G. Häberl introduces his new publication and offers an insight into Mandaean History in this blog post.

The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran first emerge into view from the marshy lands at the head of the Persian Gulf. There, they distinguish themselves from their neighbors primarily through their unique religious beliefs and their language, a form of Aramaic which they record in a script that is similarly unique to them. Among their scriptures, they esteem the Genzā Rabbā or ‘Great Treasure’ as the most sacred. These scriptures have been the subject of sustained interest from non-Mandaean scholars for more than two centuries, beginning with Matthias Norberg’s pioneer edition and translation of the Genzā Rabbā in 1815. The editions and translations that followed his are considered landmarks in the history of Philology, and banner examples of the philological enterprise, one that processes and thereby subsumes data from texts such as these into its own episteme toward a variety of uses—linguistic, literary, and at times historical.

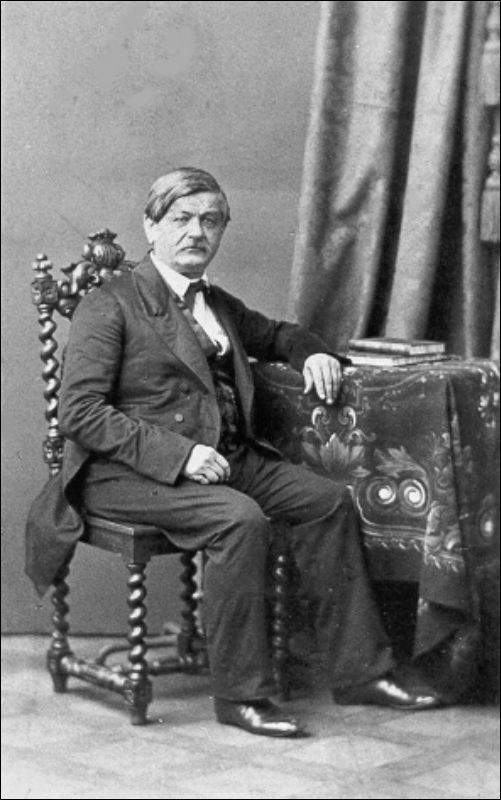

In the last vein, generations of scholars have concluded that Mandaeans ‘have no history books’ and that their own histories are ‘naturally replete with fabrications of all kinds’, in the words of the celebrated German philologist J. Heinrich Petermann, who produced the critical edition of the Genzā Rabbā that has served as the last word on the subject until the present date. What then is the value of a new translation, in a series explicitly for the benefit of historians?

Public Domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

In Walter Benjamin’s formulation, the common task of translators and historians alike is to recognize the truth-content of a text and actualize it, making it present in every sense. Although generations of philologists such as Norberg, Petermann, Theodor Nöldeke, Mark Lidzbarski, and Rudolf Macuch have cast aspersions on the truth-content of Mandaean literature and wrought a kind of epistemic violence against it, for no reason other than the fact that it exists on the other side of a divide defined and policed by our own notions of the rational and scientific, we have also long recognized that it contains within it scientific knowledge of a sort: seemingly naïve, insufficiently elaborated, and falling short of the level established by our own factitious standards of scientificity, but nonetheless dimly recognizable as scientific discourse, and therefore speaking to us in a different sort of language than the alien faith of the Mandaeans and its gnostic tenets. This discourse consists of a chronology of various and sundry rulers, dated records of earthquakes, famines, and pestilences, and observations of astronomical phenomena, among other things.

We have conditioned ourselves to attribute a certain power to such discourse reflexively, but few have essayed to engage the scientific discourse within this Mandaean text and ‘actualize’ it, comprehending it in terms familiar to us and highlighting its present relevance for our own enterprises, including our reckoning of the region’s history. In Foucauldian terms, the ‘subjugated knowledge’ represented by the various philological editions and translations of this text yet paradoxically disguised within them presents an opportunity to critique those same works of scholarship and by extension the entire enterprise of scholarship on Mandaeans, if only we could understand what it is saying to us across the epistemic divide. Because of longstanding Mandaean engagements with the surrounding communities—Zoroastrians, Jews, Christians, and Muslims—these texts plainly have much to say about the history of those communities and other subjects of interest and relevance to historians working on an array of periods and places, regardless of whether we have been listening.

In The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World, by appealing to the scientific discourse within the Genzā Rabbā and engaging it to actualize the text for new audiences, I demonstrate that it is not merely a unique source for the study of Mandaean history, but also an untapped resource for the political, economic, and social history of the later Sasanian empire, the history of the Arabs of Mesopotamia on the eve of the Muslim conquest, and the history of Arabic and Persian literature in the early Islamic era, particularly with regard to the Persian national epic, the Shāhnāmeh. Obviously, such discourse does not characterize every Mandaean text, but nonetheless I hope to have illustrated how such texts still have much to say to us, and how a more charitable approach to their study can still reveal new and valuable insights even after more than two centuries of sustained scholarly interest.

Find out more about Charles Häberl’s new book The Book of Kings and the Explanations of This World on the LUP website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk