A City Against Empire is the history of the anti-imperialist movement in 1920s Mexico City. It combines intellectual, social, and urban history to analyse the city’s role as an important global hub for anti-imperialism, exile activism, political art, and international solidarity. In the blog post, author Thomas K. Lindner introduces this new Open Access publication and shares insight on its key arguments.

At first sight, the cover of A City Against Empire features sombreros and a newspaper. On closer inspection, one recognizes the skeptical look of a male peasant towards the onlooker and perhaps even the newspaper’s name El Machete and its headline ¡Toda la Tierra, no Pedazos de Tierra! (The whole land, not pieces of it!). The picture was taken by the American-Italian photographer and communist Tina Modotti in the streets of Mexico City. Published in 1928 with the title “Campesinos Reading El Machete”, it shows the act of collective reading. Symbolically, Modotti conceals the readers’ faces by focusing on their sombreros: not individuals, but the whole working proletariat is reading the communist newspaper and land redistribution is a topic discussed in the streets. I chose this image as book cover because it gives us a brief glimpse of the way radicalism was experienced in the streets of Mexico City. In my book, I intend to engage with radical transnational activism and ask how people used the city, its streets and neighborhoods to engage with the global topic of empire.

The book focuses on anti-imperialists. But who was an anti-imperialist and what did anti-imperialism mean in the context of Mexico City in the 1920s? For me, anti-imperialists were those who expressed their opposition to imperialism and elevated this concern into a central part of their political identity. Communists who criticized capitalism, progressives who defended the Mexican Constitution of 1917, and Mexican presidents who talked about the nationalization of oil companies did so in a language of anti-imperialism. Clearly, not all of these actors shared all political opinions, but anti-imperialism was inclusive (or vague, one could say) enough to be combined with many other world views. For me, this elusive and sometimes even contradictory nature makes anti-imperialism a fascinating topic that sheds light on diverse actors who often did not agree with each other.

Opposing empire and fighting for a just world order was en vogue in the 1920s. After the First World War, Europe had clearly lost its claim to any kind of “civilizing mission” as European colonialism was increasingly criticized, and the military and fiscal actions of the United States came under scrutiny around the world. Anti-imperialism was an attractive ideology for radical activists, artists, and intellectuals just when Mexico City became the perfect place to live anti-imperialist activism. Different Mexican governments supported anti-imperialism, many Latin and US American exiles used it to build connections, anticolonialists viewed it as the global force for the twentieth century and proletarian activists viewed anti-imperialism as a way to unite working people across race, class, and gender boundaries. Many anti-imperialist activists (like Tina Modotti, Julio Antonio Mella, Anita Brenner, Alfons Goldschmidt, José Vasconcelos, Pandurang Khankhoje to name a few) lived in Mexico in the 1920s and collectively made Mexico City the city of anti-imperialism.

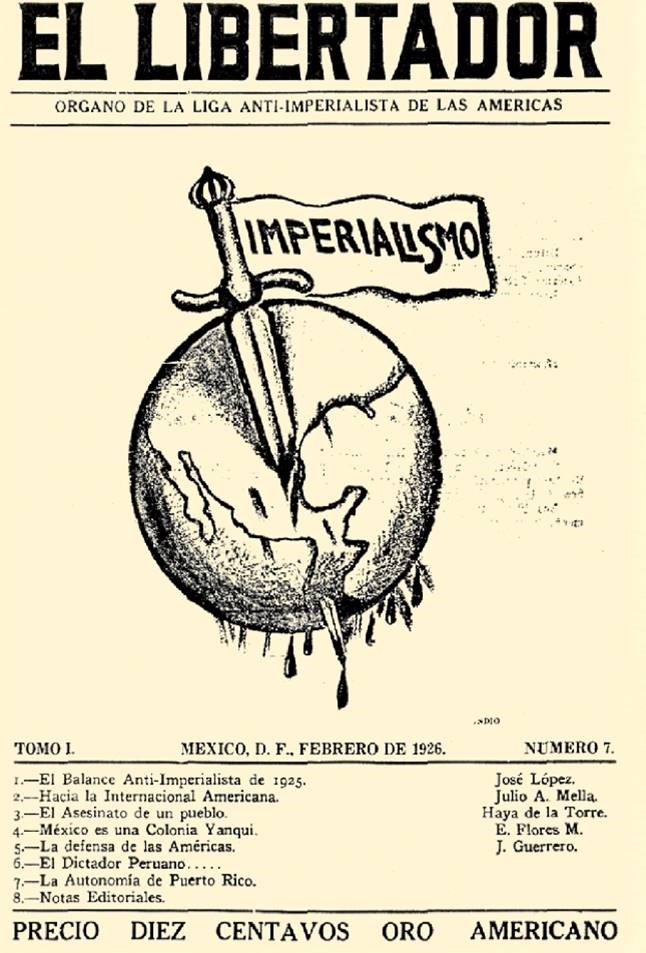

I analyze the perfect storm of transnational anti-imperialism in the 1920s using social and urban history. I felt that a perspective on intellectual history or the history of ideas would not be able to adequately portray the role anti-imperialism occupied in Mexico City. For example, political exiles from Cuba, Venezuela, and Peru lived together in a house in the Calle Bolívar – just across the offices of El Libertador, the anti-imperialist newspaper that connected different radical fights. The shared apartments, the restaurants and cafés, the newspaper offices and the art workshops were spaces of radical sociability that connected different ideas and people across the city. Mexico City in the 1920s was a fascinating place with ties to the whole world. To engage with both the local setting and the global connections in the city is the aim of this book. If you are interested in the history of Mexico City, radical transnationalism in the 1920s or the history of anti-imperialist thought, please consider giving the book a look. It is, after all, available via Open Access and ready to be shared, discussed, and criticized.

Thomas K. Lindner

Thomas K. Lindner is currently working as Wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter (Postdoc / Lecturer) at the Historical Institute of the University of Rostock. He is working on a second book about the global history of worker sports, 1880-1940.

Find out more about A City Against Empire on the Liverpool University Press website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk