Grounded in a fine-grained analysis of contemporary Indian fiction, Beyond Alterity: Contemporary Indian Fiction and the Neoliberal Script by Shakti Jaising argues that the logic of neoliberal capitalism and the steady proliferation of its ideological script have produced significant continuities in class dynamics, subjective experience, as well as literary and cultural expression across the North-South divide. In this blog post, Shakti Jaising introduces the book and situates India within the wider context of neoliberalism.

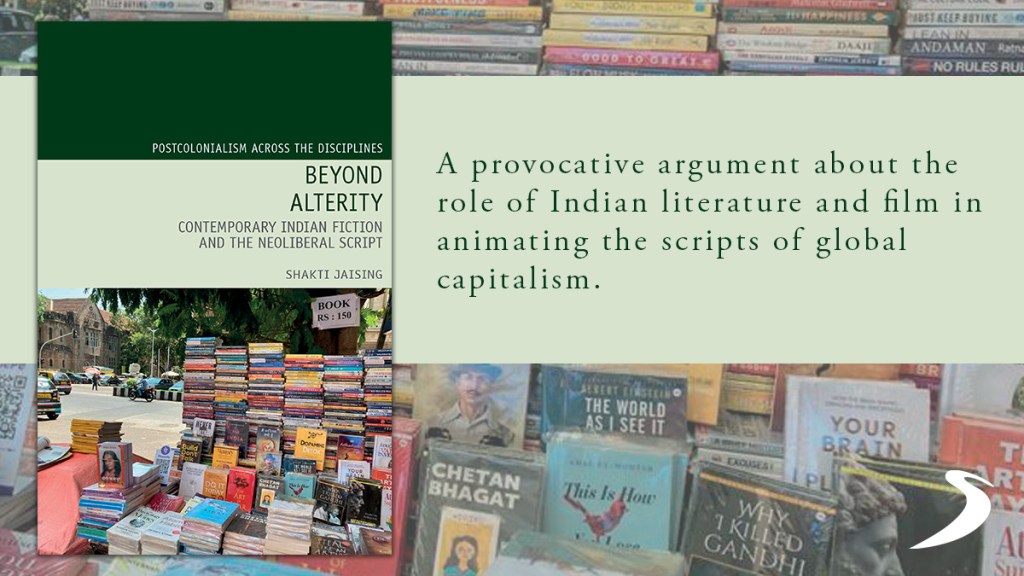

Beyond Alterity: Contemporary Indian Fiction and the Neoliberal Script explores how culture and consciousness have been impacted, particularly in India’s case, by economic transformations of the last four decades. The book’s cover includes a photo I took recently of a street bookshop in Mumbai. Here the novels of Chetan Bhagat—the biggest-selling Indian English-language novelist—appear as the sole examples of fiction amidst memoirs like Why I Killed Gandhi and Autobiography of a Yogi, as well as self-help titles like Build Don’t Talk and Steal Like an Artist. For me, this street display encapsulates the manner in which genres of imaginative writing like the Indian English novel have been subsumed by the broader ethos of neoliberal capitalism. Whereas the Anglophone Indian novel is often framed as an exemplar of postcolonial resistance, Beyond Alterity argues that the genre’s contemporary examples offer less an easy model of resistance than a vital means of insight into the entanglements between literature and neoliberalism.

Over the last decade and a half, much scholarship in the humanities has been devoted to understanding the neoliberal turn and its effects on subjectivity and cultural production. The bulk of this scholarship has focused on the advanced capitalist world and its hyper-individualism; the developing world is either left out or assumed to be distinct or exceptional. For influential political theorist Wendy Brown, neoliberalism in the North is characterized by the normalization of individualist values via the exercise of “soft power,” whereas in the South it has entailed the imposition of “hard power” or overt domination. In another influential study, Aihwa Ong complicates such clear opposition between North and South; yet, Ong nevertheless privileges contrasts over continuities in neoliberal formations across the North-South divide. Beyond Alterity draws chiefly on examples from neoliberal India— a quintessential Southern economy— to make the case that continuities in class dynamics, experience, and expression between the neoliberalizing North and South are at least as deserving of our attention as differences emanating from the legacies of colonialism.

To begin with, I propose that neoliberalism is much more than a species of individualism. In fact, were it so, it is unlikely to have earned the kind of social legitimacy it enjoys in much of the world. Through India’s example I show how neoliberalism is, in Jamie Peck’s words, a “constructed” project—constructed, that is, by national elites in conjunction with their global counterparts. Crucial to this constructed project has been the proliferation of what I call a neoliberal “script” or ideational sequence that positions private enterprise, as opposed to state-led redistribution, as the ideal means of ensuring progress for both individuals and nations. In India, repeated performances of this script have helped to promote policies of deregulation, privatization, and austerity as progressivesolutions—elixirs for treating all manner of collective problems, including poverty and underdevelopment. This claim to transforming the plight of the collectivity, particularly of the poor, has proven to be especially insidious, enabling neoliberal ideas to resonate in a variety of contexts, including in the global South.

The neoliberal script has proliferated partly through genres like the Anglophone Indian novel, together with its audiovisual adaptations. Whereas much of the book traces interactions between Indian texts and the neoliberal script, it begins by showing this script at work in Free to Choose, Chicago School economist Milton Friedman’s documentary series, which premiered on US public television in 1980. I point especially to how Free to Choose’s utopian portrait of capitalism relies on scenes of abject poverty in India, whose late-20th century developmental state is made to function as a dystopian “other” to the free market ideal. Friedman likens central planning in India to welfare in the US and Britain, arguing that both forms of government intervention produce rather than remedy poverty.

This performance of the neoliberal script is far from singular, however. Following economic liberalization in India during the 1990s, a Friedmanesque understanding of the causes and solutions to poverty haunts the discourse of economists and leaders like Manmohan Singh, as well as of professionals and representatives of the business class like Gurcharan Das. The “national biography”—which includes Das’s India Unbound (2000) and India Grows at Night (2013)—emerges as a popular genre. Circulating partly through translation, especially among the middle class, such books help to promote the image of India as a new nation, rising from the ashes of the developmental state, or “License Raj.” The dissemination of such narratives has allowed national elites to justify austerity and privatization as the only available responses to deepening unemployment, underemployment, and inequality. More recently, these narratives have fed the reigning rhetoric of Hindu nationalism and enabled the far-right government’s abdication of responsibility to the private sector.

Alongside the “national biography,” Bildungsromane tracing the maturation of socially conscious entrepreneurial protagonists gain currency with the Indian middle class. In the bestselling novels of Bhagat, which have flooded India’s domestic publishing market over the last two decades and even been adapted to Hindi cinema, the maturing entrepreneurs are typically middle class, often from small towns, and representative of the nation’s “emergence” out of the stagnation engendered by a misguided state. In other cases, like Vikas Swarup’s Q&A (2005)—which was adapted into the global hit, Slumdog Millionaire— an impoverished entrepreneurial figure rises from the chaos of India’s invisibilized “undercities” and becomes emblematic of “new” India. Even in a formally complex, “literary” novel like Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide (2004) a neoliberal script is discernable, as enterprising metropolitans develop a social conscience through their encounters with rural poverty and histories of state violence. At the same time that fiction like Swarup’s and Ghosh’s exposes longstanding corruption together with existing divides, it also shores up the belief that relief from poverty and a more just social order hinge ultimately on the personal maturation of enterprising subjects.

While Beyond Alterity centers the Indian English novel, it also explores this genre’s ties to commodified cultural production from other neoliberalizing contexts, including the United States, South Africa, and Brazil. But in attending to imaginative literature’s role in proliferating the neoliberal script, the book does not thereby imply that this is all that literature does or can do. Also important to its analysis are the formal means by which writers like Aravind Adiga and Arundhati Roy contend with growing inequality by satirizing, fragmenting, or inverting the rags-to-riches plot and related formats for narrating personal and national emergence. All too often, fiction like Roy’s and Adiga’s is seen as exemplary of all literature from the South, which is assumed to be “writing back” to the West. What Beyond Alterity demonstrates is that such assumptions overlook the literary field’s operation within a “field of power” or “social field,” as Pierre Bourdieu put it, which increasingly links the South to—as opposed to distinguishing it from—the North. In the end, the book’s attention to continuities across the North-South divide serves to bring into focus the global rise of far-right authoritarian regimes. For these regimes have everywhere been fueled by, what Pankaj Mishra describes as, mounting ressentiment, stemming from a widely-perceived gap between the narratives and the realities of neoliberal capitalism.

Shakti Jaising

Shakti Jaising is an Associate Professor of English and Film Studies at Drew University, USA.

Find out more about Beyond Alterity on the Liverpool University Press website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk