Only 20 years old when she first set foot on Northern Irish soil as part of a university exchange, Elizabeth DeYoung (now Dr. DeYoung) spent months getting accustomed to the paths, people, and pubs of Belfast. It wasn’t until her return, years later, during a chance conversation with an old landlord, that she learned of the Girdwood Army Barracks. In this blog post, the author of Power, Politics and Territory in the ‘New Northern Ireland’ retraces her steps across the city, giving an insight into how governmental failures prevented the Barracks from enacting real change, and how community groups are currently endeavouring to right this wrong.

Each morning in Belfast, I laced up my boots and shrugged on a jacket, picked a direction and walked for hours. I took long, circuitous routes to meetings and plotted far-flung paths to distant neighborhoods. I walked up to the cemeteries and down to the docks, past boarded-up houses and corner shops and chip shops and betting shops. I moved through narrow streets tagged with graffiti. I planned pilgrimages to find obscure murals and paused to read memorial plaques, strange arbiters between past and present.

Sometimes I felt invisible on these walks, as if I could move through walls. And I often did, passing through interface barriers (‘peace walls’) and crossing visible and invisible boundaries from one place to the next. Other times, I felt very obvious, indeed, disoriented and confused in spaces where I did not belong. On one of my walks, I got hopelessly lost. Intending to cut through a side street, I found instead a solid wall of metal sheeting. It looked like a peace wall but there was no logical reason for the barrier in that part of North Belfast. It was out of place. I retreated awkwardly, hoping no one had noticed my small navigational failure. I found later that the metal sheeting was the perimeter wall of the demilitarized Girdwood Army Barracks. Over the years that followed that initial encounter, I became committed to piecing together the story of Girdwood.

The Barracks sit in highly contested territory between several neighborhoods segregated by ethno-national identity and traumatized by violent conflict. The site had offered an internationally significant opportunity to put the promises of the Good Friday Agreement into practice. Here were 27 acres of land to build on – space to invest in marginalized communities, employ transformative peace-building practices, and (perhaps most importantly) build affordable housing. North Belfast had long experienced a severe housing crisis and thousands languished on the waiting list.

“The power-sharing government, led by the DUP and Sinn Féin, was more concerned with resource competition and identity politics than redevelopment plans.”

For years, activist group Participation and the Practice of Rights (PPR) had campaigned for a human-rights based approach to development at Girdwood, including social housing. Other community groups advocated for resources targeted to the needs of residents around the site. Their work fell on deaf ears. The power-sharing government, led by the DUP and Sinn Féin, was more concerned with resource competition and identity politics than redevelopment plans. Their squabbles around territorial claim at Girdwood eventually squandered the site’s transformative potential.

After eleven years and £11.7 million of EU peace-building funds, a leisure center, the ‘Girdwood Community Hub’ opened on the site in 2016 – a weak and ineffectual ‘white elephant’ that has done little for the surrounding area. Only 60 houses were built to address massive housing need. Throughout the process, skullduggery, sectarianism and general dysfunction abounded. I followed as an observer as it all unfolded, my access facilitated in large part by the generosity of community workers and activists in the neighbourhoods around the site. They invited me to meetings and working sessions, year on year, brought me along to tour the building site and provided critical context on its history. And I kept walking, becoming deeply familiar with the geography of the area and the physicality of the Girdwood site.

The resulting book explores the Girdwood Barracks’ regeneration as an allegory for the failure of politics to deliver a ‘shared future’ for the people of Northern Ireland in the wake of the peace process. It suggests, too, that the same political dynamics that shaped Girdwood left Northern Ireland adrift during Brexit and the pandemic and led to the Northern Ireland Assembly’s collapse.

However, though the Girdwood Hub sits empty and the Assembly sits silent, new voices and demands have sprung up in Northern Ireland. PPR has continued to organize around housing justice. Other local movements have formed around Irish language rights, equal marriage, bodily autonomy, refugee and asylum-seekers’ rights, and climate justice. Community groups work to fill the systemic gaps left by politicians. More recently, an enormous swell of support and solidarity has taken place in response to the humanitarian crisis in Palestine. And these forces are visible on the streets and in the neighborhoods of Belfast.

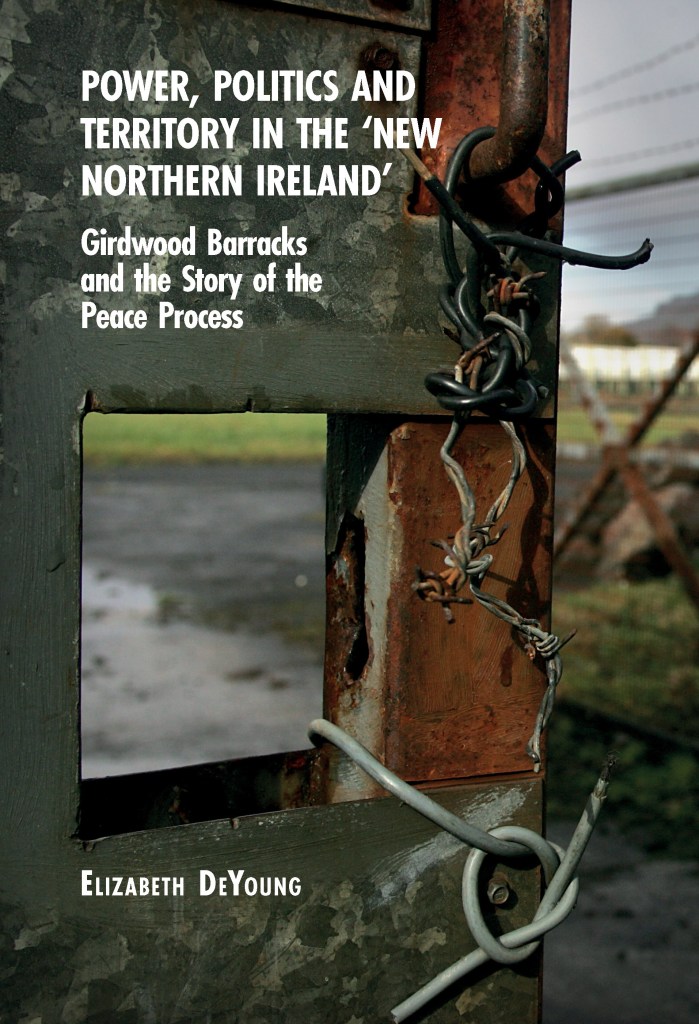

The book’s cover is a picture of the Barracks taken by a local photographer before it was redeveloped, when it sat in limbo because of political dispute. As you open the cover, a friend observed, it’s like you’re opening the gate into the development itself. My hope is that this book provides a glimpse at the inner workings of not only the Girdwood site but of post-Agreement Northern Ireland, with all its convoluted twists and turns. I wanted to bring the reader on a walk like the ones I used to take, traversing Belfast’s divides and moving from the past into the present day.

Elizabeth DeYoung is a Research Scientist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Guaranteed Income Research, where she uses qualitative and mixed methods to evaluate the effects of guaranteed income (GI) pilots in cities across the US. She holds a PhD from the Institute of Irish Studies, University of Liverpool.

Elizabeth will be launching her new book, Power, Politics and Territory in the ‘New Northern Ireland’, at The Institute of Irish Studies on February 1st. Find out more and register for the free event here. The book is available to buy now.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk