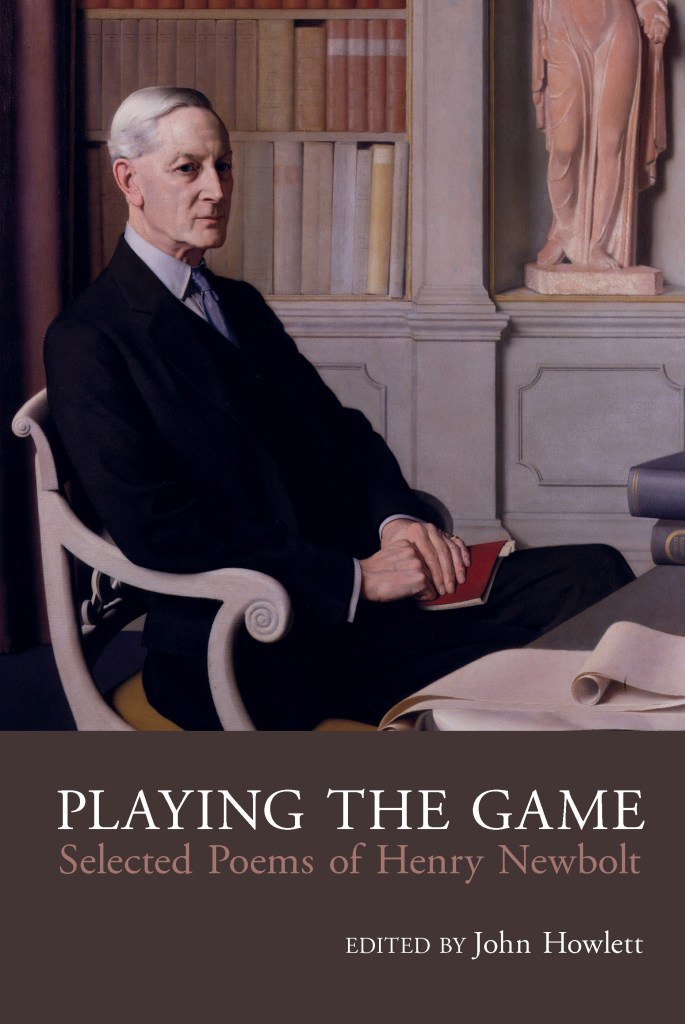

Playing the Game: Selected Poems of Henry Newbolt edited by John Howlett is the first scholarly edition in more than four decades of one of the most significant poets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To celebrate the publication of this new book, Howlett explains why Newbolt was such a figure of importance in his own time, why he has slipped into critical neglect, and why he remains vital for both contemporary readers of poetry and scholars of the Victorian period.

Until as recently as the decade following the Second World War, the poems of Henry Newbolt (1862-1938) were staples of many of the key anthologies of English verse. In particular, his two most famous pieces – ‘Drake’s Drum’ and ‘Vitaï Lampada’ – were able to be recited by most schoolchildren, even if this amounted to being able only to recall the latter’s immortal refrain of ‘Play up! play up! and play the game!’ Newbolt’s popularity was such that his early volumes of poetry not only sold in larger numbers than any of his contemporaries but he became the nation’s unofficial laureate, rubbing shoulders with the leading politicians and literary figures of the day.

Much of this popularity can be attributed to the fact that he served, at least early on, as a mouthpiece for many of the views held by society of the time; a pride in England’s glorious past, a belief in the necessity of order and Empire, and, most importantly of all, a commitment to particular codes of behaviour which had decency, fair play, and honour at their heart. Often these views were inculcated within the public schools, institutions which Newbolt saw as ideal spaces by which to promote the sorts of courage and service he deemed vital to a healthy society. Furthermore, like Kipling with whom he has often been compared, his best poems were simple (although not simplistic – the distinction is key), often in the form of the ballad, and were therefore easily accessible to readers who otherwise may not have engaged with serious literature.

In that light, it is perhaps easy to therefore see why his reputation has in more recent times gone into steep decline. Today, a dimmer view is, rightly or wrongly, taken of the British Empire and those of the past who sought to advocate for its virtues whilst the understanding of what it means to be patriotic has changed. Values of chivalry and stoicism are likewise seen as outdated and public schools no longer thought of as worthy of emulation.

And yet, when we delve deeper into Newbolt’s work, and avoid the common fallacy of judging the past by the standards of the present, a different picture emerges and one which should serve to see Newbolt rehabilitated or, at the very least, re-considered in a more serious light. First, it should be remembered that Newbolt was not the buffer of popular myth; he was a committed Liberal and attached himself to various causes seen at the time as progressive including Irish Home Rule, women’s suffrage, and radical education. Second, he was no bigot and did not believe in subjugation or conquest; rather, he championed a mutually supportive arrangement of states more akin to the modern-day Commonwealth. Finally, whilst his obsession with public schools was idiosyncratic, it was not done out of any sense of elitism, but simply as an extension of his firmly held belief in the desirability of particular virtues being passed on from generation to generation. Lest it be forgotten that ‘Vitaï Lampada’ translates as ‘torch of life’, with Newbolt the moraliser handing over its message to his readership.

As with the life; so with the poetry. What should not be denied – content and sentiment notwithstanding – is the consummate skill of Newbolt the lithe craftsman whose verses always betrayed a mastery of various types of form and meter. His poetry was, equally, democratic appealing as it did to a wider, increasingly literate, working-class readership. Most significant of all, critical appreciation of Newbolt has tended to take his early patriotic poems as symptomatic of his entire career and has thus failed to account for the subtle ways in which his poetry changed with the ages. This is understandable; these verses were, after all, the most well-known and were frequently printed in the mainstream press such that they became events. However as the pomp of the Victorian age transformed into the more ambivalent Edwardian so too do we see a comparable shift in Newbolt’s work. His poetry became more insular, more questioning, less certain. The Boer War for example was not an event to be cheered on as it was in the jingoism of contemporaries like Alfred Austin, W.E. Henley, and even Swinburne. Instead, it was to be commemorated with dignity and driven by Newbolt’s greater awareness (through his connections to both politics and education) of the sacrifices being undertaken by young men, many of whom would not return.

It was however no coincidence that as his poetry embraced wider moods – including a number of exquisite love lyrics as well as some light satire – so did his sales decline. This gradual fall from public acclaim was to be completed by the First World War, an event which fully unmade Newbolt. Although 1914 did admittedly see a brief revival in interest with his patriotic poems being re-printed so as to tap into the clamour to join up and see action, this was swiftly shown to have been a false dawn. The world was by now a markedly different place; modernism was in full swing and new modes of combat – the machine gun, poison gas, tanks, trenches – were soon to be deployed. Newbolt’s long-held vision of warfare as a fluid game with rules designed to ensure fair play and in which men displaying courage and chivalry would not be found wanting was dead. Although Newbolt was always a champion of new forms of writing, and his work at the Admiralty and Naval Intelligence gave him privileged insight into the often-stagnant military situation, he could never quite come to terms intellectually with these wider social changes. Indeed, the last book of verse published in his lifetime, a curious mixture of the tired heroic and the elegiac and fittingly titled St. George’s Day, appeared in 1918 to barely a whimper.

The remainder of Newbolt’s life was then lived out in the shadow of these crumbling beliefs; more time was spent in his country retreats of Somerset and Wiltshire and the few poems produced until his death – amongst his very best – were comparably inward-looking and signalled a retreat from the world. He had rapidly become an anachronism and he died quietly following a long illness in 1938.

That being said, as the famous literature scholar Jerome Buckley long ago attested, ‘Newbolt transcended the frantic bluster of the mere jingo’ and in so doing he offers us today, through his poetry, a window on a period of transformation in British history as the certainties of the Victorian era, which included certainties around her glorious place and role in the world, extended into the Edwardian period and a new century. Within the full gamete of his writing – as well as in the trajectory of his life – Newbolt was able to capture these transformations and his loss of a poetic voice after 1918 was therefore suggestive of something lost that was bigger than one man. In his loss however he provided a window on what Britain had been and the beliefs which drove her forward. He both reflected and shaped the age of which he was a part. That alone is surely worthy of reclamation.

John Howlett is a lecturer in Education Studies at the University of Keele.

Playing the Game: Selected Poems of Henry Newbolt is available to order on our website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk