William Jennings’ Dibia’s World: Life on an Early Sugar Plantation has recently published in the Liverpool Studies in International Slavery series. Drawing on an unpublished planter’s manuscript, this work discusses the origins, names, relationships, families, skills and health of a hundred slaves on an early sugar plantation. We spoke to author William Jennings about this new publication.

Firstly, could you tell us a bit about Dibia’s World: Life on an Early Sugar Plantation and who Dibia was?

Dibia was an African man taken across the Atlantic in the 1670s and sold into slavery on a sugar plantation. The masters, who usually allocated their slaves European names, called him Dibia, a sign of respect because in the Igbo culture where he most likely came from, a dibia is an expert—a doctor or scientist. He worked hard and was rewarded with a wife, a young woman from Senegal named Izabelle, and they had a son named Paul. They were part of an incredibly diverse community of nearly a hundred people who came from places as far apart as the Amazon, the Sahara and the Congo. They had different languages and cultures and under the extreme pressure of slavery, they had to figure out how to communicate and how to survive. Dibia’s World investigates that community: people’s origins, experiences, relationships, children, food, health, daily life and, of course, the work routines that overshadowed their existence. I try to tell the story from within the community by focusing on individuals and moments in their lives. This doesn’t mean losing sight of the bigger picture, however. I mention the voyage of the Saint-François that killed 229 of the 396 Africans on board, but I also wonder about the stress experienced by one of the survivors, 17-year-old Athiam, when she was first taken to the plantation and saw only foreigners because no one from her region had ever been shipped to the colony before.

What is the importance of having Dibia’s community documented here in your new book?

It’s very rare to have so much detail about an early sugar plantation. This book provides a counterpoint to many other studies of enslaved communities in the Atlantic world, which tend to focus on the century prior to abolition because that’s where most of the documentation is. Those later communities had a core of Creole (locally-born) adults, whose language and cultural practices had formed in the New World from African, European and Native American elements. But Dibia’s community was new. The colony, Cayenne, on the South American mainland, was only a few decades old and some people on the plantation were from just the second slave ship to sell African people there. There were almost no locally-born adults in the slave population and people would have been negotiating cultural practices and solving communication problems. In short, Dibia’s World shows an African community on the cusp of becoming African-American.

This book uses a broad range of sources, from missionary accounts to seventeenth-century scraps of paper – are there any materials which particularly stood out to you that you could discuss further with us?

As a researcher you’re constantly questioning your sources. Are they authentic? Are they reliable? What is the author’s bias? The main source for the book is a planter’s manuscript from the 1690s and I had to make sure I could trust it. Some scraps of paper that had found their way into the manuscript helped, as did the planter’s maps, which could only have been drawn by someone on the plantation. The shipping he mentioned agreed with French port archives, while missionary letters and colonial correspondence also supported the document’s authenticity and filled in some gaps. But my favourite point of confirmation was astronomical. The planter described what he called an extraordinary lunar eclipse and when I checked NASA data, I found that a rare type of lunar eclipse had taken place on exactly the date mentioned, and in addition, Cayenne was the best place in the world to see it.

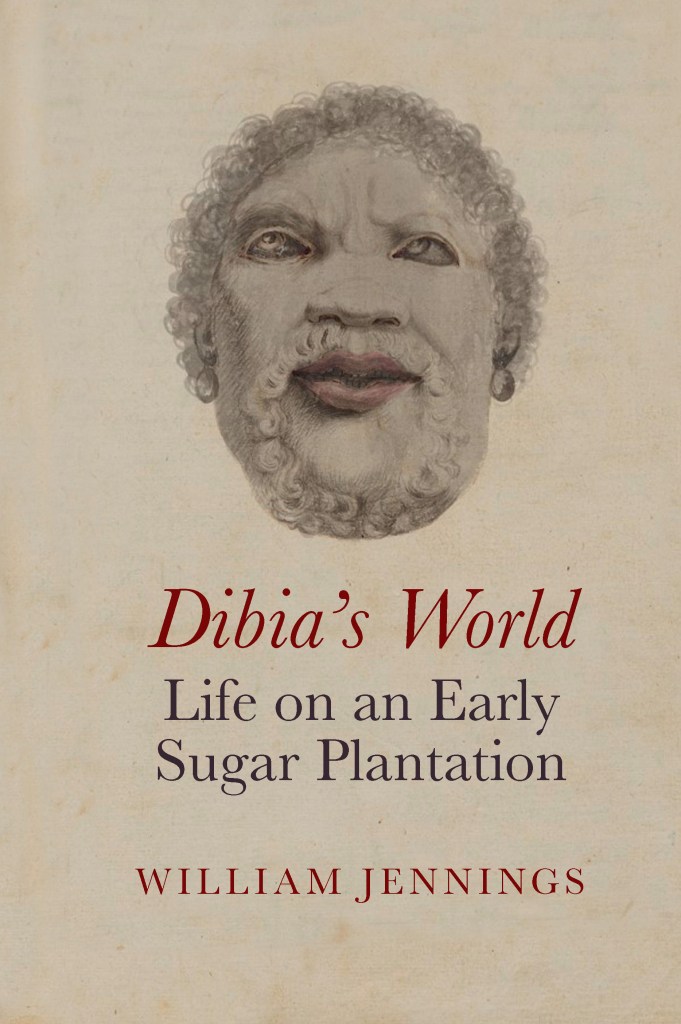

Could you tell us more about the image on the cover and why you chose it to illustrate your book?

Most early images of enslaved Africans depict them as labour units cutting cane or carrying bundles. Sometimes they are shown chained, masked or hanging to illustrate a new kind of punishment. But the image on the cover of Dibia’s World is the careful portrait of an individual done by the planter who wrote the manuscript, who was a skilled illustrator. It’s a shame he didn’t say who the subject was; he provided a biography of every enslaved person on the plantation and his manuscript shows that he considered them all as individuals with different personalities.

How does your work on Dibia’s World pave the way for further research on the topic?

I hope the book will encourage more research into early enslaved communities, which were quite different to the communities of later centuries. In particular, planters considered slave pregnancy, childbirth and childcare as impediments to productivity on early plantations. In the nineteenth century, after the slave trade was abolished, they switched to a pro-natalist policy because they realised they could no longer import captives from Africa.

Now that your book has published, what are you going to be working on next?

My research for the final chapter of Dibia’s World, on the planters, showed me that many of the colony’s free population did not travel there by choice or experience freedom on arrival. They were indentured servants, soldiers and convicts, along with women from workhouses shipped out to be married on arrival. I’d like to find out more about their lives and what they can tell us about the early colonial world.

Find out more about William Jennings’ new book Dibia’s World: Life on an Early Sugar Plantation on our website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk