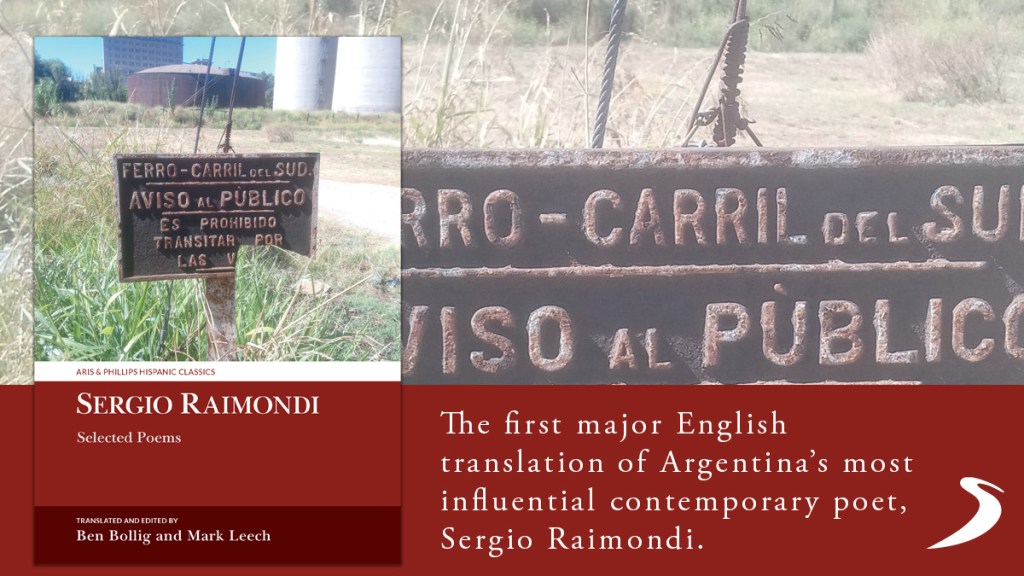

Sergio Raimondi is Argentina’s most important and influential contemporary poet, with an international reputation. Sergio Raimondi, Selected Poems brings much of his major works Poesía civil (Civil Poetry) and Lexikón (Lexikon) into English for the first time, accompanied by a translators’ introduction that puts his poetry in its literary and wider cultural context. In this blog post, editors Ben Bollig and Mark Leech introduce the book, sharing insight on the editing and translation process.

Part One: How Forms Question Structures

I first encountered Sergio Raimondi’s work at the start of the 2000s. His collection Poesía civil (Civil Poetry) felt like a watershed moment in Latin American literature, the culmination of long-running debates about how to write poetry, and something genuinely new: a book that attempted to put the whole life of a community, the Atlantic coastal town of Bahía Blanca in the province of Buenos Aires, and its cultural and political context, into poems. Bahía Blanca is at once a very conservative place, and one alive with poetry, publishing, and popular culture, and Sergio as director of the local oral history museum (the Museo del Puerto de Ingeniero White), and later as the city’s Director of Culture, was at the heart of this.

Poesía civil was feted and influential partly because Sergio managed to overcome an impasse between the two contrasting –rival even– movements or tendencies that had dominated Argentine poetry up to that moment: a plain, stripped-down, colloquial style called “objectivism” or “Poetry of the 90s”, and the more florid and sensuous neo-baroquemode of writing. Sergio, who trained as a classicist and has translated Catullus and recently Lucretius, writes in carefully measured, exquisitely crafted verses; but his subject matter encompasses everything from industrial processes to parenthood, from food legislation to fishing practices: nothing human is alien to his poetry.

I initially translated Sergio’s writing for the Poetry International Festival, Rotterdam, and for a small artisanal anthology published by Eloísa Cartonera, a cardboard-recyclers’ publishing collective based in La Boca, Buenos Aires. When Sergio told me about his project Lexikón, a 400-page alphabetical poetic encyclopaedia, ranging globally and historically on a far greater scale than Poesía civil, I started to think about a larger volume. But there were formal and stylistic aspects of the poems that I didn’t think I would be able to get quite right on my own, so I got in touch with Mark about the project.

I’d first worked with Mark when, with Alejandra Crosta, I translated his poems into Spanish for a collection of British and Irish poetry published by Espacio Hudson in Chubut, Argentina. I knew he was interested in Spanish-language poetry and translation, too. We then worked on translations together, including Ezequiel Zaidenwerg and Mirta Rosenberg’s collection Bichos (Beasties). I thought that our different backgrounds and approaches would work well on Sergio’s poetry.

We didn’t adopt the today quite fashionable practice of splitting up the work, with the academic (me) providing plain prose for the poet (Mark) to work up into poems. Instead, we independently produced initial draft versions. In mine, I focussed closely on meaning and context, and glossed key terms and turns of phrase. Meanwhile, Mark responded to the poems as a creative writer, looking at form, rhythm and sound. We then went back and forth between the versions until we were happy with all aspects of the finished poem in English.

As we were drafting, we produced lengthy notes on key terms and aspects of the poems, and realised that many of the references would need explanation for non-specialist readers. In Lexikón, Sergio doesn’t translate the titles of poems, even those which are in non-Roman script. We wanted to preserve that initially confusing effect, but also not to leave readers totally bewildered, so these and other terms are explained. Sergio’s poems can disorient and unsettle you – he is asking us to see the world from new angles, against the grain – but the glosses will help readers with details that aren’t readily available. Like the introduction, which outlines the literary and historical context from which Sergio’s writing emerges, we hope this will give readers a way into Sergio’s extraordinary universe.

Ben Bollig

Part Two: The Word and the World

Ben’s observation that “nothing human is alien to [Sergio’s] poetry” goes right to the heart of why both Poesía Civil and Lexikón are such powerful collections. It may appear counterintuitive that Sergio uses classical meters to explore what seems to us a chaotic modern world, where “Moises S. Rodríguez… brushes pavement and tarmac” (“Meditation on the Port Loading Statistics”) to glean a few grains of wheat, and “southern or western farmers” in despair at falling crop prices drink “herbicide as if it were exquisite rum” (अनियमितता).

However, these poems continually return to systems and processes. Those individuals are not the victims of chance, rather they are caught up within the machines of state and corporate interests, which like the shipping lanes in “Bulk-Carrier” are global “energetic shifts of supply and demand”. Even the tools specifically created to serve the machines fall victim when those interests move elsewhere, like the Panamax cargo ship “Built to maximise the space permitted to pass / the gates of that famous canal”, but which now “is history.”

In considering how Sergio’s work expresses its engagement with these concerns, I am reminded of two Anglophone comments: William Carlos Williams’ “a poem is a machine made of words”; and Coleridge’s description of poetry as “the best words in the best order.” Both of these thoughts find their echoes in “Transport Costs” (“the poem too is a commodity / made with a specific material”), and “Literature Will Be Subject to Investigation”:

“Poetry and ironwork,

screwdriver and vowel, metonym set

at 220v, a vice

round a metaphor being hammered straight.

The tools for the job are not finished yet.”

As Ben discusses in his introduction to our translations, Sergio is acutely conscious of poetry’s tangential relationship to this machinery of nation state and capital, and the potential for it to become irrelevant as a consequence of this indirect, even paradoxical, interaction:

“The question of the relationship between verse and the daily lot of its readers is one that we see exercising Raimondi throughout his work. Poetry, as unacknowledged legislator of the world, to use Shelley’s term, can instead become quite simply unacknowledged, which is to say, obsolete.”

These poems defy this obsolescence, in part through their content, but also through their form.

It was fundamental to our project from the start that we should respect the formal elements of Sergio’s poetry, even though we did not attempt to transplant them directly from Spanish to English. For example, in Poesía Civil, Sergio frequently uses the rhythms of Latin hexameter and the intricate syntax he developed in his earliest poetry and his translations of Catullus. In Lexikón, he uses couplets, tercets, quatrains and other stanza forms, and the echoes of Latin versification are never far away. Rather than forcing our English versions into these shapes, we worked to echo them through meters embedded in the Anglophone tradition – iambic pentameter, English alexandrines, even the Elizabethan “fourteener”, among others.

For me, the strict form of these poems has two main effects. The first is the paralleling of the system described in the content in the system of the poem. When readers encounter the complexities of lineation, meter and syntax they are also directly encountering the complexity of the machine being described. When I read these poems I am consciously experiencing what it is to be part of that machine – as if a fish were temporarily to become aware of the ocean in which it swims: “that same fluidity of fish in the water” (“Fish Block”).

Second, it seems to me that the formal virtuosity demonstrated throughout Poesía Civil and Lexikón reflects the poems’ capacity to appropriate the language and structure of systems and, rather than become complicit in their functioning, ruthlessly critique them. For every moment when the poems appear to doubt themselves (“And who is this chap? could be heard / muttered in some kind of French there behind the forge” – “Receuil (des Planches)”), at another there’s a pinpointing of the absurdity and brutal indifference of the sea in which modern societies swim:

“the permanent committee of the Party Bureau

has to operate definitively within the realm of statistics

to conceptualise these deaths that are without doubt more than lamentable

as part of their demographic policy and family planning.”

(灰色气体)

This unsparing confrontation between the artifice of the verse and the artifice of the created human world does not result in an explicit call to arms – possibly bringing to mind another Anglophone comment, WH Auden’s “poetry makes nothing happen”. Yet Sergio’s poems are full of alternative visions of the world that readers might choose to dwell on: the idealistic publishing house of Allende’s Chile in “Quimantú”; the “ten thousand flavours” of indigenous potatoes in “Wanllaqsa”; the revolutionary school of “Warisata”. Perhaps most resonant for poets are the closing lines of “Autor (als Produzent)”:

“But, comrades, you’re able to understand

that the world can change, and more: you struggle

day after day for it to change, and yet

you demand a literature that stays the same?”

Everything about Sergio’s work is a challenge to simple acceptance of the world we encounter through it. His is certainly not a poetry “that stays the same”.

Nevertheless, it can’t be denied that sometimes there’s a sense of delight in crafting a precise and vivid description of systems at work, as exemplified in “Modification to the Fuel of Locomotives Built in Europe”:

“flames up to the sheet of water

surrounding the firebox roof, the force and pressure

of steam accumulating in the boiler thrown

onto the pistons in the cylinders and moved

down the smooth dynamic rod to the wheel, which turns.”

No matter how serious the questions he explores, Sergio remains an artist, whose skill and craftsmanship in themselves deserve the widest audience.

Mark Leech

Ben Bollig is a Professor of Spanish American Literature at the University of Oxford.

Mark Leech is a freelance editor and writer based in Oxford.

Find out more about Sergio Raimondi, Selected Poems on the Liverpool University Press website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk