Ancient Plaster: Casting Light on a Forgotten Sculptural Material, edited by Abbey L. R. Ellis and Emma M. Payne, offers a fresh exploration of plaster in the sculpture of the ancient Mediterranean and beyond.

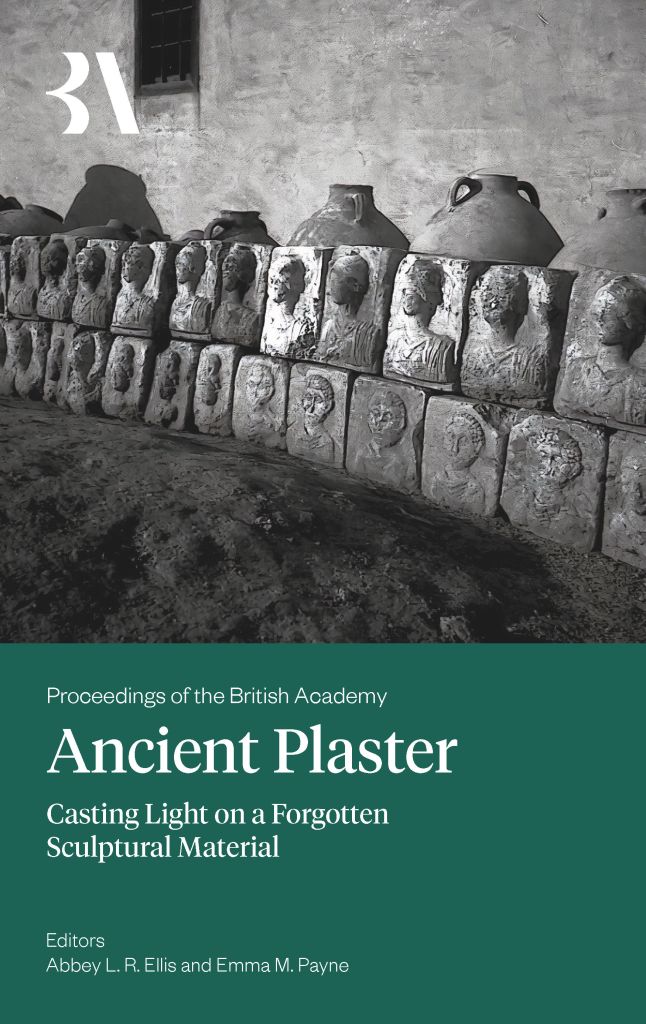

Figure 1: Plaster blocks with relief heads, excavated at the site of Dura-Europos, Syria.

Imagine wandering through the ancient sculpture galleries of a major museum—the British Museum in London or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York [figure 2]. Which materials capture your attention? Marble is an obvious candidate, stealing the spotlight with its luminous white surfaces. Bronze, too, stands out—its rich patina and subtle play of light hint at the foundries that shaped it centuries ago. Terracotta is omnipresent as well, telling its stories through exquisitely painted vases and small-scale figurines.

Figure 2: The Mary and Michael Jaharis Gallery in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, which is home to large-scale displays of Greek and Roman sculpture.

But beneath the grandeur of marble, the allure of bronze, and the solidity of terracotta, another material quietly shaped the art of the ancient Mediterranean: plaster.

The uses of plaster are so familiar in our everyday lives—from patching walls to making casts for broken limbs—that it is easy to overlook its remarkable artistic history. Yet in antiquity, plaster played a pivotal role in sculpture, both in the sculptor’s workshop and beyond—a fact that has often been neglected in academic scholarship. Unveiling this history is at the heart of Ancient Plaster: Casting Light on a Forgotten Sculptural Material, a new volume co-edited by Abbey L. R. Ellis and Emma M. Payne.

Why has plaster been so neglected? Partly, it’s down to survival: while marble, bronze, and terracotta endure for millennia, plaster is fragile and can be easily lost, often leaving only traces in the archaeological record. But it’s also about perception. Plaster is often seen as a means to an end—a material for making models, moulds, or copies, rather than for creating finished works. This book challenges that assumption, showing that ancient plaster objects were sometimes highly valued in their own right.

Many plaster casts were indeed used as tools in the transmission of artistic motifs across the ancient world—helping sculptors replicate designs from metal drinking vessels [figure 3] or earlier sculptural masterpieces. However, evidence that some ancient plaster objects served this purpose is often used to tar all such objects with the same interpretive brush. This volume argues that, in fact, some plaster objects were valuable objects intended for display, while others served ritual or commemorative purposes, taking on new meanings as they moved from a workshop setting to a temple or a tomb.

Figure 3: Plaster casts were regularly taken from vessels such as this gilded silver bowl depicting the Greek god Dionysos and the mythological princess Ariadne.

In addition to challenging some of the most common conventions about ancient plaster, one of the book’s distinctive features is the dialogue that it creates between past and present. By inviting contemporary artists [figure 4] and technicians to reflect on their own experiences with plaster, the volume draws vital connections between ancient and modern practices. These contributors emphasise the utility and value of plaster and argue that life casting—the process of taking direct plaster impressions from a living model—should not be perceived as mechanical “cheating,” a shortcut, or a means to circumvent artistic skill. Instead, their practice-based chapters show that it is a respected and legitimate tool for artists, enhancing their creative process.

Figure 4: Life cast of a hand, executed in white plaster, made using alginate.

The volume’s additional insights into life casting argue that it played a key role in sparking the shift toward striking naturalism in Classical sculpture. By combining archaeological evidence, analysis of ancient texts, and experiments in a modern foundry, it suggests that dynamic casting methods enabled unprecedented accuracy and lifelikeness in bronzes like the Riace Warriors and Delphi Charioteer [figure 5]. The volume also explores plaster death masks in Roman funerary rituals, revealing how these casts helped families negotiate memory and mourning. In short, Ancient Plaster reframes life casting as a central, creative force in the story of ancient art.

Figure 5: Bronze statue of the Delphi Charioteer displayed at the Archaeological Museum of Delphi.

Another landmark contribution within the volume comes from the late Amanda Claridge, whose arguments have the potential to transform our understanding of some of the most well-known plaster objects from antiquity: the plaster casts found at the Roman town of Baiae in the Bay of Naples. Long thought to be direct evidence of Roman sculptors copying Greek masterpieces using casts, Claridge rigorously re-examines the date, function, and interpretation of these objects, questioning the established hypotheses that surround them. Her analysis suggests that the Baiae casts may not be ancient at all and—crucially—she finds no physical evidence to confirm their use as tools for artists. This reassessment challenges a foundational narrative in the history of ancient art, urging a reconsideration of how artistic traditions and technologies were transmitted in antiquity.

For scholars, artists, and anyone interested in the history of making, this book offers a transformative perspective. It casts light on a material that, though often dismissed as humble and associated with a technique decried as “cheating,” helped shape the art of the ancient world.

Whether you are a scholar, an artist, or simply a lover of ancient art, the editors hope that this book will encourage you to look again at the objects—and the materials—that have fashioned our understanding of the past.

Ancient Plaster: Casting Light on a Forgotten Sculptural Material, edited by Abbey L. R. Ellis and Emma M. Payne, is now available on our website with a 20% discount.

Abbey L. R. Ellis is based at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ, where she has served as a Research Associate in the Krateros Squeeze Digitization Project and as a Visitor in the School of Historical Studies. Her research considers ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, plaster casts ancient and modern, and historic reproductions more generally. In 2021, she was awarded her Ph.D. by the University of Leicester’s School of Museum Studies. Her Ph.D. project focused on issues of value related to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford’s collection of archaeological plaster casts. In addition to her work at the Institute, she is a Guest Lecturer at the Princeton Academy of Art.

Emma M. Payne is a Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of Classics, King’s College London, where she also completed a Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellowship (2018–2021), exploring the making of ancient Greek and Roman stone and plaster sculpture. She completed her PhD in 2017 at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, studying the archaeological and historical significances of casts of classical sculpture. She is the author of Casting the Parthenon Sculptures from the Eighteenth Century to the Digital Age (Bloomsbury, 2021). Before her PhD, she trained as a conservator of archaeological and museum objects through which she gained a keen practical awareness of the materiality of objects. She presently works on a number of archaeological conservation projects as a freelance conservator, mainly in the southeast of England.

[Figure 1: Yale University Art Gallery (Neg. Nr. Dura-fV187)]

[Figure 2: Abbey Ellis]

[Figure 3: J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (Inv. Nr. 83.AM.389.1)]

[Figure 4: Martin Hanson]

[Figure 5: Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons]

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

OSE Bluesky | LUP Bluesky | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk