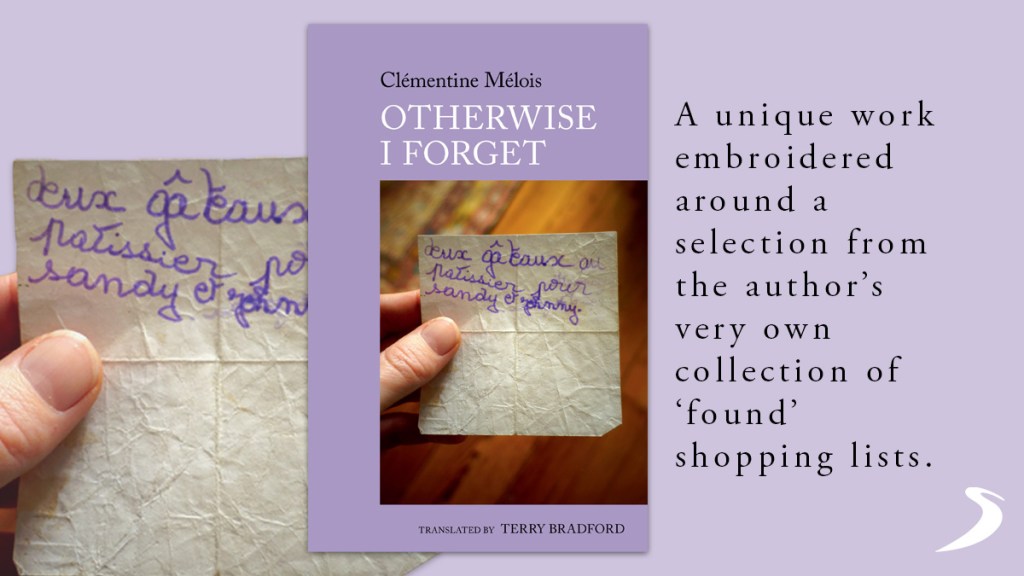

Otherwise I Forget, written by Clémentine Mélois and translated by Terry J. Bradford, is a delightful panoramic view of contemporary France. The first of her works to be translated into English, this selection of ‘found’ shopping lists spawns imagined insights into the lives and minds of their authors, and is a wonderful introduction to this highly original writer’s work. In this blog post, Terry J. Bradford gives insight into his experience as a translator, and the complexities of undergoing the translation process.

Translation has been a passion of mine since I was a teenager. On a gap year before going on to study for my degree in French and Spanish, I worked in an old people’s home in Belgium. Doesn’t everyone? While there, the head nurse – Madame Cornant – asked me to translate a song from The Sound of Music into French… Understanding that a literal translation of ‘doe, a deer, a female deer, ray, a drop of golden sun’ did not make for a functioning translation – in the sense that the child-friendly explanation of the musical scale was lost – came as a revelation (the French word for ‘doe’ is ‘biche’, so a literal translation misses the point that a word sounding like a musical note – ‘do’ – is being used to explain the scale, ‘do-re-mi’…). Armed only with my A-level French, I understood the utter necessity of creativity in the process of adapting a given text (with a given function) for a new audience.

Thirty-five years on from that epiphany, I find myself teaching French and translation at the University of Leeds. I have been translating professionally since 2001, but only recently have I begun to try my hand at literary translation. My translation of Boris Vian’s Vercoquin and the Plankton was published in 2022 by Wakefield Press (USA), and I am grateful to Liverpool University Press for publishing my latest translation of Clémentine Mélois’ Sinon j’oublie – the first of her works to be published in English.

I found out about the work of Clémentine Mélois very tangentially through research into Boris Vian’s unfinished novel On n’y échappe pas. Mélois had produced the cover for an edition of the novel completed by members of Oulipo in 2020. I treated myself to a few of her books; I loved them. What I loved was the sense of humour and the sense of play in her work – both as an artist and as a writer. A funny – and very silly – example: in Cent titres (literally ‘A Hundred Titles’, but also a pun on ‘sans titre’ – ‘untitled’) she subverts the titles and artwork of iconic French editions of novels. Each adapted cover is accompanied by a tongue-in-cheek commentary. One of my favourites is the French folio edition of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Now titled ‘Maudit Bic’ – an inventive Spoonerism signifying ‘Damned pen’ – the whale of the original cover has been replaced by the infuriated scribble of someone trying to get a pen to work.

What I found outstanding about Sinon j’oublie (Otherwise I Forget) was its premise – so original and so seemingly simple! After a short foreword – part autobiography, part introduction to her modus operandi – we find a hundred photographs of shopping lists that Clémentine Mélois has found. In the foreword, we learn that these are but a selection from her collection – built up over a period of years – which she keeps in a number of old shoe boxes. Each list is accompanied by a transcription of what the list ‘says’ – with spelling mistakes and all – and a short piece of writing giving an imagined insight into each author’s life.

Rarely if ever do the characters come across as stereotypical – which, I imagine, is the trap in the design of this project. Thanks to particular details, and perhaps thanks to the presence of the genuine artefacts that are the shopping lists – at which one finds oneself glancing when reading the text – the characters come to life. They might even remind us of people we know. And this, despite the fact that the characters are ostensibly French, immersed – of course – in a different culture.

And that – for me – was one of the attractions of translating this book: the challenge of communicating at once the uniqueness – and cultural specificity – of each character for other (anglophone) cultures, whilst allowing our common humanity to shine through. Furthermore, I enjoyed the challenge of resisting the easy temptation to ‘domesticate’ the characters and myriad references to French culture – for example, by ‘translating’ French brands with ‘equivalent’ products found in Britain. Rather than erasing cultural difference, I saw this as an opportunity to celebrate it.

I have always been a ‘people person’, and I am still fascinated by the ways in which people express themselves – their accent, their use of idiom and non-standard language (including dialect and regionalisms). The sociolinguistic landscape in France is very different to that in the UK – and I certainly did not wish to impose recognisable regional accents on the characters in English. Even so, I have had fun in using non-standard English – for example, ‘undercrackers’ for underpants – and idiom (some a little arcane), in order to give relief to the characters in English. Balancing this, I believe the texts should be open enough to be read in a variety of accents in English – on the page, the texts should read differently to different readers. But were it to be adapted for the stage, it would work well – I imagine – as a literary/theatrical form of UK TV programme Gogglebox (I am indebted to my 12-year-old daughter, Ella, for introducing me to this voyeuristic insight into varieties of contemporary English.)

To some extent, the presence of the lists – together with their transcription – imposes a constraint on the part of the translator. As the Source Texts of the shopping lists remain present (in French), and the reader can see them – where usually, in translation, the original is buried, replaced, or covered by the text of the translation itself – the translator runs the risk of confusing the reader if the ‘translation’ is manifestly at odds with what the reader can see. Generally, what I sought to do was adapt certain items which I guessed might be opaque for anglophone audiences, but keep more transparent items. For example, ‘huile colza’ is rendered as ‘rapeseed oil’ – thus communicating the sense of this item whilst respecting syntactical differences between French and English – but the item ‘Biscottes’ is retained.

Clémentine Mélois is herself a member of Oulipo – a select group of writers united in experimenting with ‘constrained’ literature. Perhaps the most famous example of such work is the novel La Disparition, created by former member of Oulipo, Georges Perec. The constraint or challenge, here, was to write a novel without using the most common letter in the French language: ‘e’. Amusingly, an unwitting translator – who might translate the title literally into English as ‘The Disappearance’ – would fall over in the starting blocks. This is worth mentioning because Mélois’ kinship with Perec unlocks some of the hidden complexity at work in this ‘novel’.

One overt signpost to this affinity – might one add influence, inspiration? – lies in the fact that Mélois includes a quotation from Perec by way of epigraph to the text and images that follow it. Regarding the ‘infra-ordinary’, it heralds stories of ‘ordinary’ people, in their ‘everyday’ lives, wrapped up in the ‘trivia’ and ‘background noise’ of life in the present. And what could be more mundane – as a way into such lives – than the humble, disposable shopping list?

That there are a hundred such lists – as there were a hundred titles in Cent titres – is itself significant. It is an echo of the hundred spaces of the apartment block in Perec’s La Vie:mode d’emploi (‘Life: A User’s Manual’). And just as Perec generated narrative using the concept of the knight’s tour – whereby, on a 10×10 chessboard, the knight is moved in such a way that it lands only once on each of that board’s squares – we might be moved to imagine how Mélois might have used this concept to devise her characters in harness with their individual shopping lists.

Another nod to Oulipo can be discerned in one of the characters, whose story might present as a re-write of the anecdote that Raymond Queneau – founder of Oulipo – used in his Exercices de style (‘Exercises in Style’). In this work, Queneau told the same anecdote in ninety-nine different ways – that is, in different styles or with particular features, ranging from anagrams to zoological. My intention in alluding to these features of Mélois’ book is certainly not to explain… I seek only to hint at the richness of Sinon j’oublie and the literary traditions – and formal experiments – in which it is rooted. My intention in translating a book like this – so subtly and cleverly crafted – transcends the mere reproduction of the stories or the words themselves. On one level, I am sure that Mélois’ characters – and their lists – will entertain us and give us food for thought. But I also hope that the uniqueness, formal inventiveness, and playfulness of this text – like so many seeds – are scattered to new fields where they might cross-pollinate.

Terry J. Bradford

Terry Bradford is Senior Lecturer in the French Department and with the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Leeds. He translated Boris Vian’s Vercoquin and the Plankton (2022).

Find out more about Otherwise I Forget on the Liverpool University Press website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk