A History of Disability in England by Simon Jarrett has recently published as part of our Historic England partnership. This thousand-year history of people with disabilities in English society ranges from the surprisingly integrated societies of the medieval and early modern periods to the institutionalisation of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This book holds important lessons for modern society as it professes to seek ‘inclusion’. In this blog post, author Simon Jarrett introduces us to this new book and discusses what we as members of modern society can learn from the history of disability.

A more inclusive past? Learning from the history of disability.

It can be tempting to think of history as a relatively straight line in which incremental progress is made from a bad past to a much better present. In my new book A History of Disability in England from the Medieval Period to the Present Day I argue that it is inaccurate to think in this way about the historical experience of disabled people. There is in fact much we can learn from some periods of the past about community inclusion and creating a culture in which ‘difference’ is woven into daily life.

For example, in the medieval period, and then the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (known as the Early Modern Period) there was no state system of institutions and little government involvement in ordinary people’s everyday lives. For this reason the locus of care and support for disabled people was in the family and community.

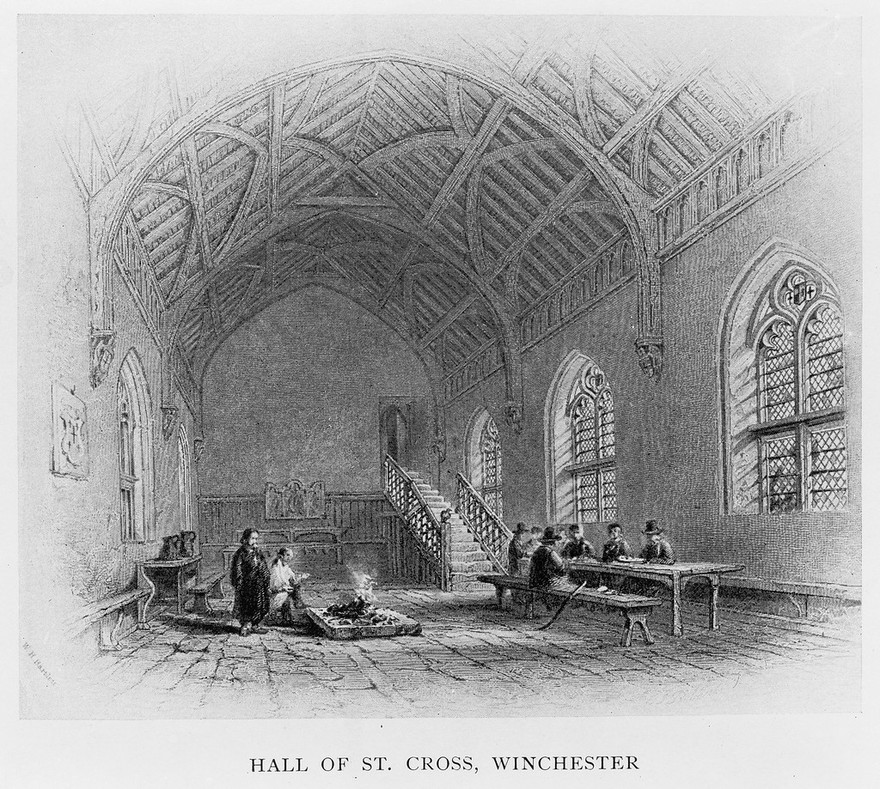

The Medieval Hospitals of England by Rotha Mary Clay: with a preface by the Lord Bishop of Bristol (1909).

Wellcome Collection.

An integrated community?

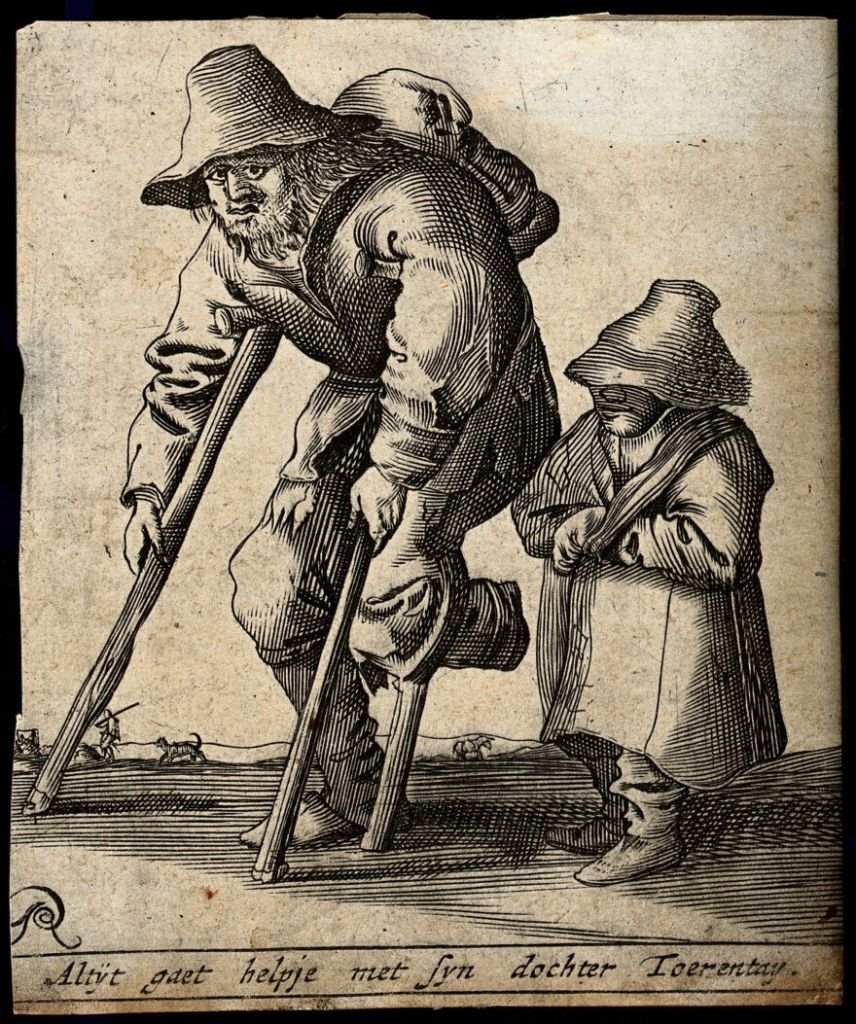

I write in the book about the Norwich ‘Census of the Poor’, which took place in 1570, twelve years after Elizabeth I came to the throne. It provided a detailed analysis, based on door-to-door surveys, of the inhabitants of the poorest areas of this commercial trading city, including its disabled residents. These were variously described as blind, deaf, ‘lame’, ‘crooked’ or lacking one or more limbs.

The majority were married, usually to non-disabled partners, and most were working, including an 80-year-old yarn spinner and a 70-year-old blind baker. The picture is one of an integrated community of disabled people. They were poor and daily life was hard, as was the case for most of the population at this time. The hardship for this group was of course exacerbated by their disabilities. However, there was no sign in the census of their being marginalised, forced out of mainstream society or seen as not belonging.

Engraving with etching by P Quast. Wellcome Collection.

Institutions were rare. One exception was so-called ‘Leper Houses’, built in the medieval period in response to the pervasive presence of leprosy (today known as Hansen’s Disease) at the time, which had disabling consequences for many. Leper Houses were run by religious orders, concentrating as much on spiritual care as physical healthcare.

Research has shown that these were generally humane and caring places which showed respect to their disabled inhabitants. Though often on the edge of towns and cities to take advantage of clean air and restful environments they were far from isolated, closely connected to nearby towns, families and passing pilgrims.

An exception of course was the famous Bethlem mental institution, (popularly known as Bedlam) which dates from the medieval period and had a reputation for cruelty and abuse over the centuries. However, horrific as it was, Bedlam always loomed larger in the popular imagination than it did in reality. The medieval building had just 12 ‘cells’ (or rooms) for patients. Most disabled people in this period never went anywhere near an institution.

Wellcome Collection.

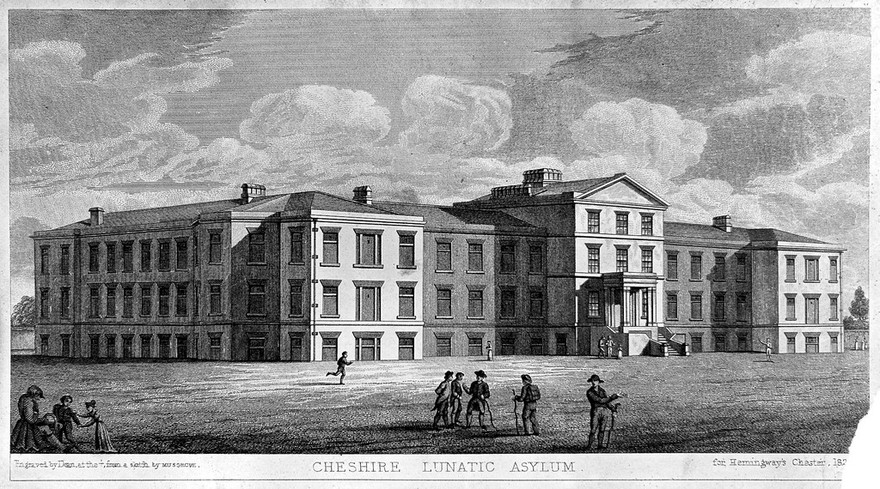

Institutions and Eugenics

The situation changed drastically in the nineteenth century when a growing state, which involved itself more proactively in the lives of ordinary citizens, began to construct a network of institutions. Asylums, workhouses and other specialist facilities were used to house those seen as different and not fit for society. From this point many disabled people were seen as not belonging, unfit to remain in the same communities as non-disabled people.

This led to disastrous consequences, The so-called ‘science’ of eugenics labelled disabled people as inferior, the consequence of ‘bad breeding’, and associated with criminality. In the twentieth century this eugenic libel spread across the western world and was widely accepted in Britain, where it originated. In Nazi Germany, where the racist ideology of Nazism collided with the beliefs of the eugenics movement, tens of thousands of disabled people were systematically killed between 1939-41, simply because they were disabled.

In other countries events were not so catastrophic, but disabled people were systematically marginalised, demonised and isolated, in schools, long-stay hospitals and other institutions. The process of de-institutionalisation did not begin in earnest until the 1980s.

The twentieth century, seen by many as a century in which humankind made many great advances, ranks as a period of darkness and struggle for many disabled people.

Improvements

Of course, it is important to acknowledge that some great things have happened in recent years. There have been big strides in making urban environments and buildings more accessible, although much remains still to be done. Despite improvements, disabled people still persistently encounter barriers to navigating the towns and cities in which they live and accessing the buildings they wish to use.

In the book I write about how innovations such as dropped kerbs, pelican crossings, accessible toilets and ramped building access came about in post-war Britain. More recently still the concept of universal design has inspired architects to design buildings and places which are fully accessible not only to disabled people but any person with any sort of mobility restriction. Access is not an add-on in such buildings and places, but at the heart of their design – think of the 2012 Olympic Stadium in London.

Courtesy of the Historic England Archive.

We have also had policy changes such as the Disability Discrimination Act of 1995, which made discrimination against disabled people illegal. There have been advances in human rights, embedded in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons of 1975, and in 2011 the European Union’s Convention on the Rights of Disabled Persons.

Learning from the past

And yet we know that despite all these gains high levels of discrimination remain today. Unemployment among disabled people is persistently high and many live in poverty. There are disturbing instances of hate crime. Institutional abuse persists. Whatever rights might have been bestowed on them, many disabled people are often made to feel they outsiders, who do not belong. In many ways, after the years of institutionalisation, we still lack an inclusive social culture.

For examples of how inclusion can work, we can learn something from studying societies of the medieval and early modern periods, unlikely as that might sound to us enlightened, progressive people of the twenty-first century.

Find out more about Simon Jarrett’s new book A History of Disability in England on the Liverpool University Press website.

Follow us for more updates

Sign up to our mailing list

Twitter | Instagram

www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk